Greece continues to impose one of the heaviest tax burdens on employment among developed nations, according to the latest Taxing Wages 2025 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The report, which tracks the relationship between labor income and taxation across the 38 OECD member states, reveals that Greek workers and their employers shoulder a disproportionately high fiscal load—one that is not matched by similarly generous social benefits or tax relief measures.

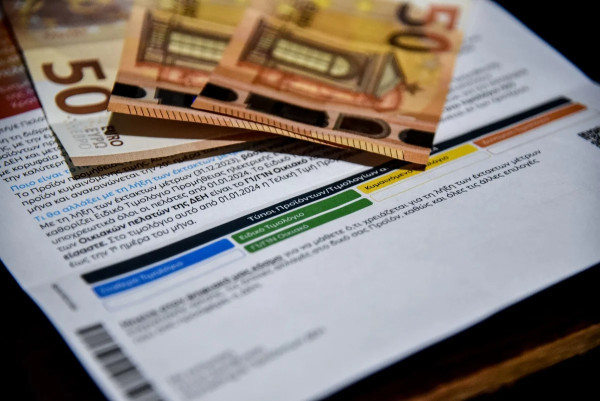

In concrete terms, a single Greek worker without children who earns the average national salary sees 39.3% of their total employment cost—the full amount an employer pays for their labor—disappear into taxes and social security contributions. That means for every €100 an employer spends, only €60.70 ends up in the employee’s pocket. The rest is claimed by the state. This puts Greece above the OECD average of 34.9%, placing it closer to countries with much higher overall taxation like Belgium, where the rate reaches 52.6%.

By contrast, other developed nations manage to impose a far lighter burden on labor. Switzerland taxes just 22.9% of the total employment cost, New Zealand 20.8%, and Chile only 7.2%. While a few European peers—such as Portugal (39.4%) and Slovenia (44.6%)—show similar or higher figures, many of these countries offset the cost with generous public services or targeted tax credits, cushioning the impact on take-home pay and quality of life.

What is particularly striking in the Greek case is that this increasing burden hasn’t come from a deliberate hike in tax rates or social contributions. Instead, it stems from a technical phenomenon known as “fiscal drag.” As nominal wages rose in Greece between 2023 and 2024, more income was pushed into higher tax brackets, but the tax thresholds and deductions were not adjusted accordingly. The result is that workers end up paying more, even though tax policy itself hasn’t formally changed.

Looking specifically at personal taxation—that is, how much of a worker’s gross salary goes directly to taxes and employee-side contributions—the figures are also telling. In 2024, a Greek employee forfeits 25.8% of their gross wage to the state. In practical terms, someone earning €1,000 a month before taxes takes home about €742, with the remaining €258 lost to deductions. This rate is slightly above the OECD average of 25%, and comparable to countries like Ireland and Sweden. Yet, unlike those countries, Greece offers far fewer compensatory mechanisms to soften the blow.

This lack of balance is one of the core issues highlighted in the OECD report. While higher-tax countries like Belgium and the Nordic nations typically provide substantial family benefits, tax breaks for parents, or generous social safety nets, Greece offers limited relief. Families with children, low-income earners, and other vulnerable groups receive fewer targeted benefits than their counterparts in many European countries. For example, Poland and Portugal have introduced well-structured tax credits that significantly ease the financial pressure on these demographics—something Greece has yet to match.