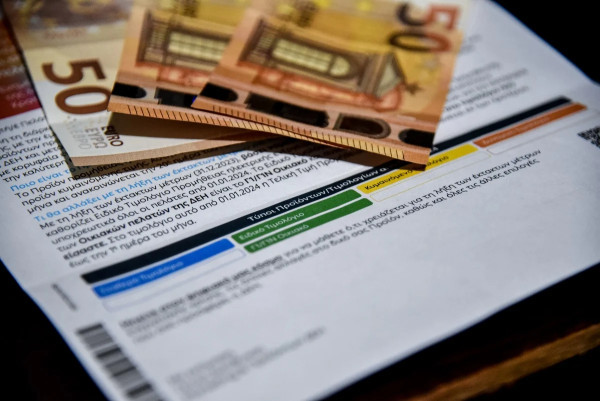

Greece’s Independent Authority for Public Revenue (AADE) is set to publish its latest list of major tax debtors—individuals and companies who owe more than €150,000 to the state and have failed to settle their debts within the deadlines provided. The release is part of an ongoing effort to pressure high-value defaulters into compliance by exposing them publicly. However, despite the intent to boost accountability and encourage repayments, the strategy of public shaming has shown limited effectiveness.

Those with smaller debts, up to €150,000, were given until June 27 to arrange payment or face similar exposure. Now, those who failed to meet the deadline will be listed alongside larger defaulters. This policy is rooted in the belief that public disclosure can serve as a deterrent, particularly for those with the financial capacity to pay but who deliberately avoid doing so. Yet, the data tell a different story.

Greece is burdened by an enormous volume of overdue tax debt—about €110 billion in total. Strikingly, 96.5% of this amount comes from debts over €10,000, and more than three-quarters—76.2%—is owed in amounts exceeding €1 million. These large debts are concentrated among just 0.2% of all tax debtors. In contrast, the vast majority of taxpayers with overdue liabilities—roughly 91%—owe relatively modest sums under €10,000, accounting for only 3.5% of the total.

The imbalance is also evident in the type of debtor. Natural persons, or individuals, are responsible for about €42.6 billion of the debt, while legal entities—mostly companies—owe €68.2 billion. Among those owing more than €1 million, businesses account for nearly 70% of the total, with over 6,000 companies falling into this high-debt category.

Despite the scale and visibility of these figures, publicizing the names of major debtors has not proven to be a meaningful solution. Only 4.3% of the outstanding tax debt has been brought under any kind of installment or repayment plan—a mere €3.6 billion—highlighting how little impact the threat of exposure has had on recovery efforts.

In many cases, those at the top of the debtor lists are so-called "strategic defaulters": individuals or entities with the means to pay, but who make a calculated choice not to. For these debtors, the reputational damage of being named publicly is minimal compared to the financial benefit of continued non-payment. Some of the companies on the list are defunct or only exist on paper, with no assets, income, or active representatives—making any meaningful recovery of funds practically impossible.

Moreover, the tactic of public disclosure holds little weight for those who do not rely on public trust or reputation in their professional or personal lives. For many, especially those without a public-facing role or business interests tied to credibility, having their name published on a government list carries no serious consequences.