The steady deterioration of Greece’s international investment position since 2019 offers a revealing snapshot of the country’s economic strategy in recent years.

For an international audience, this indicator matters because it captures how dependent an economy is on external financing - and how exposed it becomes when global conditions turn less favorable. In Greece’s case, the picture has grown more troubling despite a period that, on paper, should have been supportive: low borrowing costs in the early years, substantial inflows of European funds, and a strong rebound after the pandemic.

The growing stock of net external liabilities suggests that economic growth has not translated into a more resilient or balanced economy. Under the government of Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the emphasis of growth remained largely on tourism and real estate. These sectors generate foreign inflows and short-term momentum, but they do little to build a durable productive base or to strengthen export capacity. As a result, Greece’s long-standing structural weaknesses have persisted, leaving the economy vulnerable to shifts in global financial conditions.

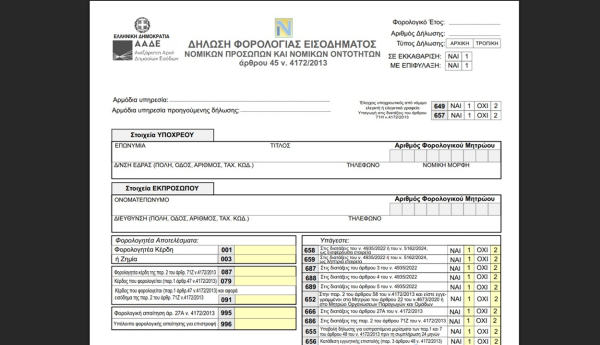

The international investment position measures the difference between what a country’s residents own abroad and what they owe to foreign investors. Greece has long recorded a deeply negative balance, reflecting high external debt and decades of current account deficits. At the end of 2019, its net position stood at roughly - €291 billion, a level that suggested some stabilization after the sovereign debt crisis of the previous decade. That fragile equilibrium was disrupted in 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. Emergency fiscal support, combined with a sharp recession, increased external borrowing, pushing the position to - €296.7 billion by year’s end.

The deterioration accelerated in 2021, when the economy was still feeling the effects of the health crisis. By the end of that year, Greece’s international investment position had fallen to - €324.2 billion, driven mainly by higher government liabilities and increased foreign holdings of Greek securities used to finance the recovery. In 2022, the trend became more volatile. Although the position worsened early in the year, it improved later on, narrowing to - €309.2 billion by December. The return of tourism, stronger exports, and valuation effects in financial markets helped offset some of the pressure, even as the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine limited the scope for sustained improvement.

The respite proved temporary. In 2023, rising global interest rates and persistent geopolitical uncertainty pushed the international investment position back to around - €327.9 billion. Early 2024 brought modest signs of stabilization, but by the final quarter the trend had reversed again, with the position deteriorating to - €325.7 billion. This decline was largely the result of higher external liabilities - particularly in portfolio and other investments - combined with adverse valuation effects amid volatile global markets.

The most recent data underline the scale of the challenge. According to the Bank of Greece, by the end of the second quarter of 2025 Greece’s net external liabilities had increased by €13.4 billion compared with the end of 2024, reaching €338.9 billion, equivalent to roughly 140 percent of GDP. For international investors and policymakers, this figure signals a high level of external exposure for a country that remains sensitive to changes in financing conditions.

Such dependence on foreign capital is not unusual for a small, open economy. What makes Greece’s case more precarious is the persistence and scale of the imbalance. A deeply negative international investment position means the country is more vulnerable to interest rate increases, shifts in investor sentiment, and sudden changes in global liquidity. Maintaining credibility with international markets therefore becomes essential, as uninterrupted access to financing is critical for the functioning of the state, the banking system, and the broader economy.

At the same time, the external position acts as a warning signal. Without a stronger export base and a more diversified productive structure, Greece is likely to continue running external deficits that require constant inflows of foreign capital. In this context, global shocks - whether geopolitical, energy-related, or financial- tend to have a disproportionate impact on the country compared with larger or more self-sufficient economies.

Improving this outlook would require a shift in strategy. Greater emphasis on export-oriented investment, higher domestic savings, productivity gains, and technological upgrading would help reduce reliance on external borrowing over time. Until such changes take root, Greece’s international investment position will continue to reflect not just short-term market dynamics, but the deeper structural limits of its growth model. For observers outside Greece, it is a reminder that headline growth figures can mask underlying vulnerabilities that only become visible when global conditions change.