Greece now occupies the unenviable position of having the highest share of citizens in Europe who spend more than 40 percent of their income on housing. At a time when property prices and rents continue to rise, the country is grappling with a deepening housing crisis marked by underinvestment in residential construction, declining homeownership, and widespread difficulty in meeting basic housing-related payments.

Each year, Eurostat measures the proportion of the population that must allocate more than 40 percent of its income to cover housing needs. The latest figures place Greece at the bottom of the European ranking. Nearly 29 percent of people living in urban areas fall into this category, compared with just 10 percent across the European Union. Rural regions provide no relief: 27.7 percent of residents in the Greek countryside are equally burdened, far above the EU average of 6 percent. Unlike countries such as Denmark and Norway, where living outside major cities significantly reduces housing pressure thanks to well-developed transport networks, Greece’s peripheral regions offer little financial advantage. Weak connections between regional areas and major urban centers mean that households cannot escape high housing costs by relocating.

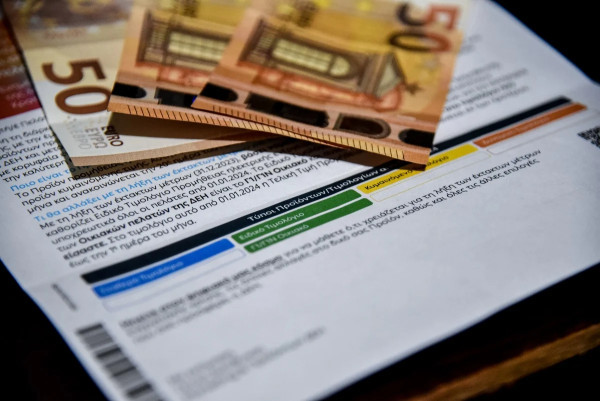

What makes the situation even more troubling is that Greece also leads Europe in unpaid housing-related bills. According to the same Eurostat report, 42.8 percent of Greeks fail to pay rent, mortgage installments, or electricity bills on time—by far the highest share in Europe and more than four times the EU average. Although this rate peaked during the financial crisis and has since declined slightly, it remains alarmingly high, a situation aggravated in recent years by soaring energy costs. This inability to cover basic expenses is reflected elsewhere: Greece is tied for the worst position in the EU when it comes to heating insecurity, with 19 percent of households unable to adequately heat their homes.

The crisis is further compounded by the erosion of one of Greece’s traditional strengths: high homeownership. For decades, owning a home offered Greek families a measure of protection against fluctuating housing prices. That advantage is fading. Homeownership has now slipped below 70 percent for the first time in years, approaching the EU average of 68.4 percent. The outlook is particularly stark when compared to countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, where homeownership rates remain exceptionally high. As more Greeks are pushed into the rental market, they face rapidly rising rents, which continue to increase even as general inflation levels off.

Perhaps the most revealing indicator of the structural nature of the crisis is the low level of investment in new housing. At a moment when demand is far outpacing supply, Greece spends just 2.6 percent of its GDP on residential construction, one of the lowest rates in Europe and less than half the EU average. Countries like Cyprus, Italy, Germany, and France invest more than 6 percent, ensuring a steady flow of new housing stock. In Greece, the lack of new construction drives prices higher and leaves families with few affordable options.