At this year’s Thessaloniki International Fair, the Greek government is preparing to unveil a package of tax relief measures, even as inflation and soaring prices continue to swell state revenues. The paradox is stark: while officials point to fiscal overperformance, the engine driving it is not economic growth but higher consumer prices, which disproportionately hit low- and middle-income households.

Over the past two years, Greece’s public finances have consistently beaten revenue targets. In 2024, the government budgeted €62.8 billion in tax income, yet actual receipts climbed to nearly €68.8 billion, an increase of 9.5 percent. A similar pattern is emerging this year. Revenues for 2025 were forecast at €69.4 billion, but are now expected to reach €75 billion, almost 8 percent above plan. Economic growth, however, remained modest, never exceeding 2.5 percent annually during this period. The conclusion is unavoidable: the surge in revenues has little to do with a more dynamic economy and everything to do with inflationary pressure, which has inflated tax intake through higher prices.

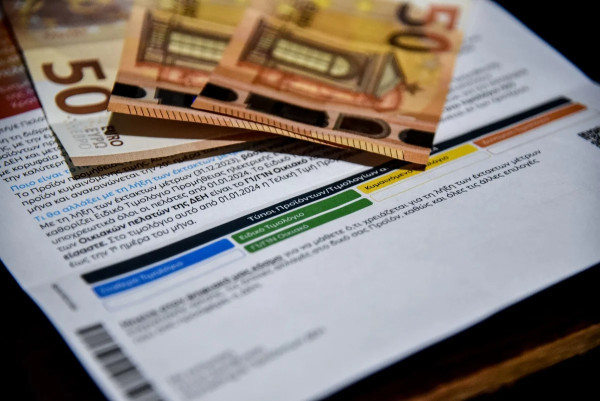

Data from the state budget show tax revenues totaling €40.6 billion between January and July 2025, compared with €36.9 billion during the same period in 2024 and €33.7 billion in 2023. That means tax collections have risen by more than €6.8 billion - or around 20 percent - in just 24 months. The clearest example comes from value-added tax (VAT), the quintessential indirect levy tied directly to consumption. Between January and June 2025, VAT receipts reached €12.9 billion, up from €11.9 billion the year before and €11 billion in 2023. In two years, VAT revenues have risen by €1.9 billion, or about 17 percent.

Because VAT is applied uniformly, regardless of income, the burden falls heaviest on those with the least purchasing power. Households that devote a larger share of their income to essential goods - where price increases have been steepest - end up shouldering the cost of fiscal outperformance. In effect, Greece’s budget stability has been underwritten by consumers, particularly those least able to afford it.

The government is now signaling new measures, including adjustments to income tax brackets and changes in the taxation of rental income, as part of its announcements at the Thessaloniki fair. Yet these pledges, while politically significant, are unlikely to resolve the underlying dilemma: a fiscal model that relies heavily on revenues generated by inflation and high prices, effectively funded from the pockets of the country’s most vulnerable citizens.