Christos Rammos, a senior judge and former president of Greece’s Authority for the Protection of the Confidentiality of Communications (ADAE), described the country’s wiretapping affair as a constitutional scandal of historic proportions and warned that its implications extended to the rights of every citizen. Speaking to journalist Rania Tzima about a case that had come to define one of the gravest crises of the rule of law in post-dictatorship Greece, Rammos argued that key aspects of the scandal were never fully investigated and remained obscured.

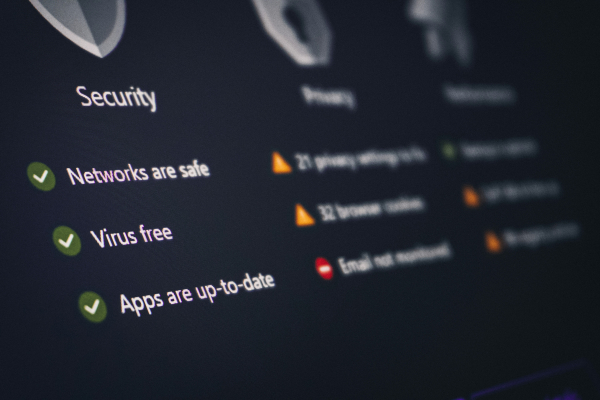

Rammos, who also served as vice president of Greece’s highest administrative court, the Council of State, was head of ADAE when revelations emerged that politicians, journalists, and other public figures had been placed under surveillance, either through the National Intelligence Service (EYP) or via the illegal spyware Predator. In an interview conducted as part of a public discussion series, he described the period as “an unprecedented retreat of the guarantees of the rule of law,” unseen since the restoration of democracy in 1974.

He said that when he assumed his role, he could not have imagined that, decades after Greece’s democratic transition and long after its integration into European institutions, the country would face a constitutional breach of such magnitude. The challenge, he noted, was compounded by the absence of established case law to guide the handling of mass surveillance abuses.

According to Rammos, efforts by ADAE to investigate the affair were actively obstructed, by Kyriakos Mitsotakis administration. He stated that the intelligence service, the government, and parts of the judiciary failed to support the authority’s mandate to uncover the truth. One of the earliest and most significant obstacles, he said, was a legal opinion issued in January 2023 by the then prosecutor of Greece’s Supreme Court, which curtailed ADAE’s ability to conduct oversight.

Rammos also expressed surprise that no political figures were charged in connection with the case. He attributed this outcome to a prosecutorial report approved by the current Supreme Court prosecutor, who described its conclusions as legally sound. For Rammos, however, the decision to absolve political actors for what were deemed “lawful — or more accurately, formally lawful — surveillance authorisations” raises serious concerns.

Equally troubling, he said, was the handling of the Predator spyware case. Prosecutors concluded that responsibility lay solely with four individuals linked to private companies involved in marketing and distributing the software. Rammos questioned the plausibility of this conclusion, noting that it is difficult to accept that such an operation could have taken place without involvement or accountability within the state apparatus. He further pointed out that the suspects faced only misdemeanor charges, rather than felony counts, a decision he described as hard to reconcile with both legal reasoning and common sense.

Asked whether the overall handling of the case suggested an effort to cover up the scandal or at least obstruct its investigation, Rammos answered in the affirmative. While awaiting final court decisions and acknowledging that the case could theoretically be reopened under specific conditions, he said bluntly that the broader truth has yet to emerge. “We have not learned the full picture,” he said. “It remains hidden.”

Rammos stopped short of claiming there was a centrally coordinated plan for mass surveillance, saying there is no conclusive evidence to support such an assertion. However, drawing on his long judicial experience, he offered a broader observation. Historically, he noted, governments that resort to such methods often do so in order to secure and preserve their hold on power, monitoring individuals who might pose a political threat. This, he argued, is precisely why democratic systems require strong institutional checks and balances.

He also addressed public voices that have sought to downplay the significance of the wiretapping affair. According to Rammos, constitutional protections do not erode all at once but gradually. Once one safeguard is weakened, others follow. He stressed that constitutions and fundamental rights exist primarily to protect the vulnerable, not the powerful, and that the violation of a single right endangers the entire framework of freedoms.

Rammos highlighted the particular importance that the Greek Constitution assigns to the confidentiality of communications, describing it as an “absolutely inviolable” right. Without trust in private communication, he argued, citizens begin to self-censor, undermining free expression, democratic participation, and personal autonomy. Surveillance of journalists, he added, directly threatens press freedom, while the monitoring of politicians can compromise democratic decision-making at the highest levels.

Finally, Rammos addressed the issue of constitutional reform, focusing on Article 86 of the Greek Constitution, which governs the criminal liability of ministers. In practice, he said, the provision has functioned less as a tool for accountability and more as a mechanism for shielding political figures from investigation. In his view, there is no viable alternative to transferring the prosecution of ministers to the ordinary judiciary, placing them before the same courts as any other citizen.