A new joint ministerial decision in Greece establishes, for the first time, a comprehensive and formal framework governing how the state may conduct covert operations against organised crime and terrorism. The regulation is signed by Michalis Chrysochoidis, the minister responsible for citizen protection, Giorgos Floridis, the justice minister, and Thanos Petralias, the deputy minister for national economy and finance.

Undercover policing is not new in Greece. For years, security services have relied on covert methods to infiltrate criminal organisations, particularly in cases involving serious organised crime or terrorism. Until now, however, the practical rules governing such operations were fragmented and often regulated internally, without a single, transparent legal framework. The new decision seeks to codify these practices, defining in detail when and how police officers — and, in certain cases, private individuals cooperating with them — may operate under false identities, engage in financial and administrative transactions and draw on public funds.

The regulation is explicitly geared towards investigations where infiltration is deemed essential. Greek authorities argue that surveillance and technical monitoring alone are often insufficient to dismantle tightly knit criminal or terrorist networks. Instead, investigators may need operatives who can convincingly pose as accomplices, intermediaries or customers in order to gain the trust of suspects. To that end, the decision permits the issuance of fake identity documents, including identity cards, passports and tax identification numbers, allowing operatives to function credibly within criminal environments.

These identities, however, are designed to be strictly temporary. Each fake identity is linked to a specific investigation and remains valid only for the duration of that case. Once an operation is concluded, the documents must be formally cancelled and destroyed. The framework explicitly rules out the existence of permanent or reusable undercover identities, a provision intended to limit long-term abuse.

Within the scope of an approved operation, undercover officers or authorised civilian collaborators are permitted to open bank accounts, rent homes or vehicles, buy and sell goods and arrange telephone and internet services in their assumed names. In effect, they are allowed to construct a fully functioning everyday life under cover, reducing the risk of exposure. These powers are not unlimited. Every action must be authorised in writing by senior officials and carefully documented. Acts that would normally attract administrative penalties are exempt from sanction when carried out lawfully within the approved framework, with the state assuming responsibility for the consequences.

A substantial part of the decision addresses a traditionally opaque area: funding. Covert operations, by their nature, require money to sustain cover identities and operational needs. Under the new rules, no funds may be released without a written decision specifying both the amount required and its intended use, issued by the head of the service conducting the investigation. Informal cash disbursements are explicitly excluded.

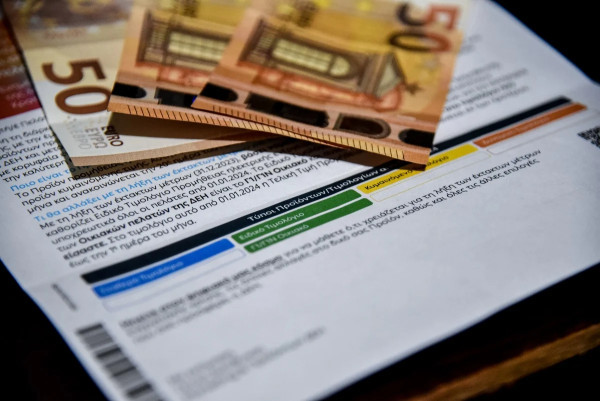

Instead, all funds are channelled through the Bank of Greece, which manages a special state account reserved for urgent matters. The competent authority must submit a confidential request stating how much money is required, for what purpose and which individual is authorised to receive it. While the operational details remain classified, the movement of public funds itself is formally recorded within the state’s financial system, creating an audit trail.

The handover of funds is documented through a delivery-and-receipt protocol, with copies retained by the central bank, the recipient and the state’s general accounting authority. During the operation, the money may be used only for approved expenses — such as accommodation, travel, purchases and services necessary to maintain cover. Where possible, receipts and other supporting documents are collected and stored in a classified file held by the relevant service.

When an operation ends, any unused funds must be returned to the Bank of Greece through a documented procedure, and the return is officially recorded. Money or assets generated through undercover activity are treated as property of the state. If an investigation leads to a conviction, those assets are permanently confiscated in favour of the public purse. If a case is closed without a conviction, a court determines their fate. Where funds are lost or cannot be adequately accounted for, an internal administrative investigation is triggered to assess whether there was misuse or whether the loss occurred despite appropriate safeguards. Only in the absence of wrongdoing does the state absorb the loss.

Despite the attempt to impose structure and accountability, the decision has sparked unease among legal scholars and practitioners, particularly over the balance it strikes between executive authority and judicial oversight. Critics argue that the judiciary is not placed at the centre of the authorisation process but is instead relegated to a largely supplementary and retrospective role.

Decisions with a direct and significant impact on fundamental rights — including the concealment of identity, the authorisation of extensive financial and administrative activity and the allocation of public funds — are primarily taken within the police and administrative hierarchy. The framework does not require prior, explicit and reasoned judicial approval for these measures. Courts and judges become involved only after a covert operation has concluded or been terminated, limiting the preventive protection that judicial scrutiny is traditionally meant to provide.

As a result, assessments of necessity and proportionality are not made in advance by an independent judicial body but are instead left to executive authorities directly involved in the operation. Although prosecutorial supervision is formally provided, legal experts argue that it often appears procedural rather than substantive, lacking robust mechanisms to ensure meaningful oversight at each critical stage. Prosecutors and investigating judges, they say, risk being reduced to actors of after-the-fact review rather than serving as primary guarantors of legality.