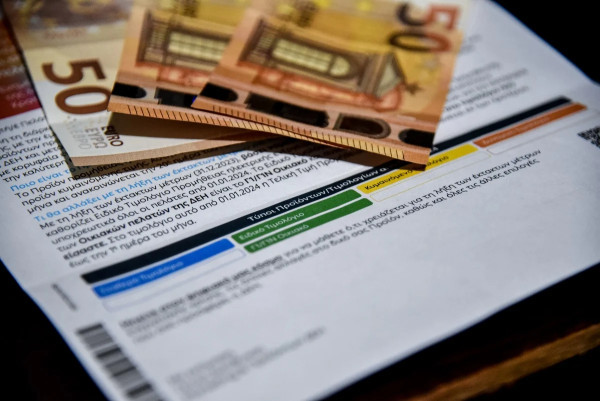

In the December 2025 payment cycle, new public-sector retirees received pensions that were on average €532 higher per month than those granted to retirees from private-sector insurance funds. One year earlier, in December 2024, the difference stood at €485, indicating a steady and ongoing expansion of the disparity.

The figures refer specifically to newly awarded pensions, meaning benefits granted to individuals who have recently retired. These pensions are calculated under current legislation and reflect recent wage levels and contribution histories, rather than older rules that applied to past generations of retirees. As a result, they offer a clear picture of how Greece’s pension system operates today and how differences in employment conditions translate into retirement income.

According to the latest data, the average gross main old-age pension for new public-sector retirees in December 2025 reached €1,425. By comparison, new retirees from private-sector insurance funds received an average gross pension of €893. In relative terms, public-sector retirees were awarded pensions that were almost 60 percent higher than those of their private-sector counterparts.

The reasons behind this gap are largely structural. Most private-sector workers in Greece retire with fewer than 40 years of insured employment, often due to periods of unemployment, part-time work, or career interruptions. By contrast, public-sector employees typically have more stable and continuous careers and tend to reach retirement with close to a full 40-year contribution record. Since years of contributions play a decisive role in pension calculations, this difference has a direct and significant impact on pension outcomes.

Differences in lifetime earnings further widen the divide. Public-sector wages in Greece are generally more stable over time and, on average, higher than those in the private sector. Higher pensionable earnings, combined with longer contribution periods, lead to larger contributory pensions for public employees under the country’s post-crisis pension rules, which closely link benefits to lifetime contributions.

Another factor weighing down private-sector pensions is the profile of new retirees. A substantial share comes from self-employment, a segment where contributions have historically been lower and insurance careers shorter. In addition, many retirees choose to repay outstanding social security debts—sometimes amounting to as much as €20,000—through monthly deductions from their pensions.

These deductions reduce the amounts actually paid and further depress the overall average for private-sector pensions.

The disparity is also evident in the pace of pension increases. A comparison between December 2024 and December 2025 shows that private-sector pensions not only start from a lower base but also grow more slowly than those in the public sector. Over this one-year period, the average new private-sector pension rose by €58, or 6.9 percent, increasing from €835 to €893. In contrast, the average new public-sector pension increased by €104, or 7.9 percent, rising from €1,320 to €1,425.

As a result, the gap between public- and private-sector pensions is widening gradually but consistently, with annual increases in the private sector amounting to roughly half those recorded in the public sector. This trend suggests that, without structural changes, the disparity is likely to persist.

The broader pension landscape in Greece remains uneven. Around 41 percent of pensioners receive a main old-age pension above €1,000 per month, while nearly 60 percent receive less than that amount. Before pension increases resumed in recent years, more than two-thirds of pensioners were below the €1,000 threshold.

Across the entire system, the average gross main old-age pension stands at €956, while the average supplementary pension amounts to €221. Taken together, the average monthly income from old-age pensions in Greece, before tax, reaches approximately €1,122.