As the new year dawned, hundreds of farmers climbed onto their tractors and positioned them along highways, junctions, and border routes, turning critical transport arteries into improvised protest camps. The message was unmistakable: this is not a symbolic gesture, but a struggle they describe as existential.

From the northeastern region of Evros to the island of Crete, and from the plains of Thessaly to the Peloponnese, the landscape looks much the same. Tractor engines remain running through freezing nights, small fires burn to keep the cold at bay, and the mood is one of accumulated anger. Many farmers say openly that they feel they have exhausted all other options.

The focal point of the mobilization is the Nikaia interchange near Larissa, long regarded as the nerve center of Greek agricultural protests. Another major blockade has formed in Kastro, in central Greece, drawing producers from across the region. Near Greece’s northern borders, tractors have also been lined up close to customs checkpoints, signaling that the issue is not only national but European in scope.

So far, farmers have sought to avoid alienating the wider public during the holiday period. They have refrained from fully closing roads, acknowledging the need for families to travel. Protesters stress that their goal is to make the crisis visible, not to punish ordinary citizens. Yet the quiet, immovable presence of heavy machinery along key routes serves as a clear warning that escalation remains on the table.

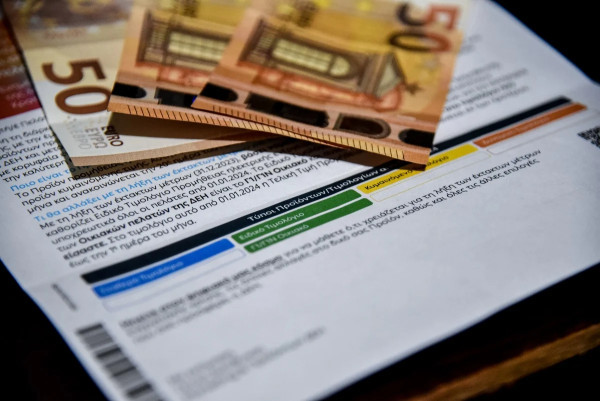

At the heart of the protest lies the sharp rise in production costs. Energy, fuel, and agricultural inputs have become so expensive, farmers argue, that cultivation is no longer sustainable. Profit margins have vanished, debts are growing, and many fear they will not be able to plant the next season. As a result, January is already being described as a decisive and potentially explosive month for rural Greece.

The pressure is particularly intense in Thessaly, where large areas of farmland remain damaged months after devastating floods caused by Storm Daniel. Fields are still unusable, and compensation payments—where they have been issued—are widely seen as falling far short of the losses suffered in crops and livestock. For many farmers in the region, recovery has barely begun.

Tensions have also been fueled by the rollout of the European Union’s revised Common Agricultural Policy. In Greece, its implementation has been marked by bureaucratic confusion, delayed payments, and reduced subsidies, reinforcing the sense among farmers that decisions made far from their fields are threatening their livelihoods.

On January 1, another sensitive change came into force. The agricultural payments authority OPEKEPE was placed under the supervision of the national tax authority, AADE. The government has framed the move as a reform aimed at transparency and efficiency. Farmers, however, are deeply distrustful. After years of delayed subsidies and technical errors, many fear that stricter controls without parallel financial support will result in further cuts and exclusions. Their refrain at the blockades is blunt: they need liquidity to sow their fields, not more platforms and inspections.

For now, the situation remains tense but controlled. That restraint is widely seen as temporary. All eyes are now fixed on Sunday, January 4, when farmers from across the country are due to meet in a nationwide assembly. That gathering is expected to determine the form the struggle will take next. Some are pushing for full highway closures and a coordinated move toward Athens, while others are waiting to see whether the government signals any willingness to engage meaningfully.

The government, meanwhile, is preparing for a harder line. Officials close to the prime minister have spoken of a so-called “Plan B,” involving fines and other sanctions against farmers whose tractors obstruct transport and commerce. Government sources stress that such measures have not yet been implemented, but emphasize that they remain an option if the protests continue after the holiday period.

Government spokesperson Pavlos Marinakis has publicly argued that tougher consequences may be unavoidable for those who, in the government’s view, reject dialogue. He has warned that protest actions causing disruption could lead to legal and administrative penalties, as has happened in past mobilizations.

At the same time, the government has sought to frame the issue as one affecting society as a whole. In his New Year’s address, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis spoke of “blockades against society,” emphasizing the rights of travelers and taxpayers to open roads. Officials have repeatedly stressed that the state must balance farmers’ demands with the needs of citizens whose daily lives are disrupted.

Another element of the government’s strategy appears to be time. There is a clear expectation that fatigue and economic pressure will eventually weaken the protests. Alongside this, officials have tried to minimize the scale of the mobilization, noting that only a small proportion of Greece’s approximately 400,000 professional farmers are present at the blockades. Mitsotakis has insisted that the government must also engage with the majority of farmers and livestock breeders who are not protesting but face real difficulties of their own.

Rhetoric from senior ministers has further inflamed the situation. Health Minister Adonis Georgiadis has launched blunt attacks on the protesters, describing them as a small and extreme minority and accusing them of inflicting serious damage on local economies. His comments have drawn criticism for deepening polarization rather than encouraging dialogue.

Within the ruling party, there is growing concern about the political cost of the confrontation. Lawmakers privately acknowledge that the agricultural front is beginning to affect wider government plans. A cabinet reshuffle that had been expected after the holidays is now effectively frozen, with senior officials suggesting that no major changes can be made while the standoff with farmers remains unresolved. Additional uncertainty stems from pending legal developments related to agricultural subsidies, which could further complicate the political picture.

As farmers wait for the January 4 assembly, the atmosphere along Greece’s highways remains charged. For those gathered around their tractors in the winter cold, this is not a seasonal ritual but a fight over survival. The new year has begun with a clear signal from the countryside: patience has run out, and the next move is imminent.