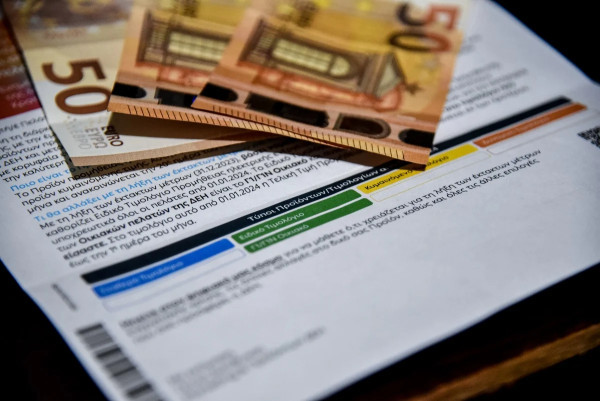

Despite a global rise in interest rates since the pandemic—conditions under which savers should be seeing significantly higher returns—Greek banks continue to offer almost nothing to those who keep their money in deposit accounts. As a result, savers find that not only is their nest egg failing to grow, but its real value is shrinking, exposing a striking disconnect between the strengthened position of the banking sector and the negligible benefits reaching the public.

In September 2025, the average weighted interest rate on new deposits was stuck at just 0.30%. This figure barely reflects the actual cost of money in the eurozone and translates into an annual gain of only three euros for every thousand euros held in a basic savings or checking account. Such a nominal return is entirely erased by inflation, leaving real returns deeply negative and steadily weakening households’ purchasing power.

Yet despite these meager yields, deposits held by Greek households and businesses remain at historically high levels, reaching €151.2 billion and €52.5 billion respectively—and exceeding €216 billion when government deposits are included. This large pool of liquidity provides banks with a robust cushion and reduces their need to compete for new deposit inflows. Coupled with a limited degree of competition in the domestic market, the environment keeps deposit rates far below international norms and out of line with public expectations.

A comparison with the period before the financial crisis illustrates the shift. In October 2008, the average rate on new deposits was 3.30%, almost ten times higher than today. At that time, a depositor could earn €33 annually for every thousand euros saved, compared with only €3 now. The contrast underscores how dramatically the relationship between banks and savers has changed, and how different the banking landscape looked during a phase of rapid credit expansion and intense competition.

Following the onset of Greece’s debt crisis—and particularly from 2015 onward—deposit rates remained anchored near zero, shaped by years of negative interest rates and quantitative easing in the eurozone. Although the European Central Bank began raising rates aggressively in 2022 to curb inflation, Greek banks transmitted only a small fraction of those increases to deposit products, taking advantage of abundant liquidity and a diminished need to raise funds.

The result is that deposits remain a safe but wholly unprofitable option, with savers watching their money lose value in real terms. The era of meaningful interest income has not just ended; it has been replaced by a new normal in which savings serve largely as idle capital rather than a source of returns.

Meanwhile, banks themselves are enjoying robust profit margins. In September 2025, the average weighted lending rate climbed to 5.73%—nearly nineteen times higher than the deposit rate. This unusually large spread highlights the substantial boost to bank profitability and is rarely seen in recent decades.

In this equation, the winners are clear: banks benefit from cheap capital and high lending returns. The losers, just as clearly, are the depositors, who bear the cost of a system that rewards them less than ever before.