Greece is beginning to feel the effects of a major shift in how the eurozone’s financial system evaluates risk. According to new analysis from the European Central Bank, the energy performance of companies and buildings has become a core factor in determining access to financing. Banks across the eurozone report that they now systematically integrate climate-related risks into their lending criteria - a change that is set to have outsized consequences in Greece, where much of the building stock is old and energy-inefficient.

The ECB’s latest lending survey shows that companies with a low environmental footprint, or with credible plans for a green transition, are increasingly rewarded with more favorable borrowing terms. Banks view these firms as less exposed to regulatory shifts or climate-related disruptions, leading to lower interest rates and faster loan approvals. High-emission sectors, or businesses making little progress on decarbonization, face tighter conditions as banks try to shield their portfolios from long-term risks.

This divide is also shaping loan demand. Firms investing in clean technologies are seeking more financing, while carbon-intensive companies are growing more cautious, wary of upcoming compliance requirements and the costs associated with meeting new standards. The ECB notes that environmental performance is now emerging as a central economic criterion in Europe’s corporate-finance landscape.

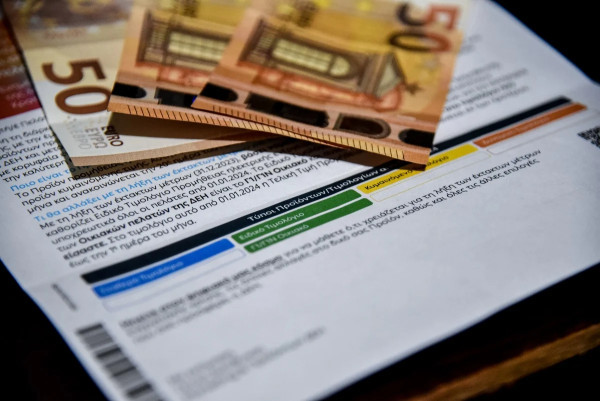

The same dynamic is visible in the mortgage market. Energy-efficient homes - either newly built or recently renovated - are securing more advantageous lending terms. Older properties, which dominate Greece’s urban centers, are treated with greater caution. They face higher interest rates, stricter evaluations, and in some cases, more limited access to credit. Banks are not only looking at energy consumption but also at the climate vulnerability of each location, including flood exposure, heatwaves, and other extreme weather events that could affect a property’s long-term value.

For Greece, the implications are significant. The overwhelming majority of homes were built between the 1970s and the late 2000s, long before modern energy standards were adopted. Only about 8 percent of the housing stock has been constructed since 2010, meaning very few properties meet the high energy-efficiency thresholds now prioritized by banks. As a result, most buyers inevitably turn to older homes - assets that lenders now classify as higher-risk, making them more expensive to finance.

The pressure is compounded by Greece’s subdued construction activity over the past decade, which has sharply limited the supply of modern, energy-performant homes. The few that exist are attracting intense demand and rapidly rising prices, making them increasingly difficult to purchase with a mortgage. Older buildings, already lagging in energy performance, are also more exposed to natural-disaster risks, further weighing on banks’ assessments.

Together, these forces are reshaping Greece’s mortgage landscape. Borrowing is no longer determined solely by a household’s income or credit profile, but increasingly by the energy and climate resilience of the property itself - raising the bar for buyers in a country where modern, efficient housing remains in short supply.