Former Greek prime minister Antonis Samaras has re-emerged as one of the fiercest critics of the Mitsotakis government, levelling accusations of ideological drift, institutional arrogance and mishandling of national tragedies—while pointedly leaving open the possibility that he may help form a new political party.

In a wide-ranging Sunday interview on Ant1, Samaras launched a scathing critique of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and the government’s response to the 2023 Tempi train disaster, which killed 57 people and continues to shape Greek public opinion. He accused the government of treating the victims’ families “with insensitivity,” arguing that the tragedy has scarred the nation’s collective memory, particularly among younger Greeks. The loss of his own daughter, Lena, he said, deepened his connection to the families still seeking justice.

Samaras rejected any suggestion that his rift with Mitsotakis is personal. Instead, he framed it as a struggle over the identity of New Democracy (ND), Greece’s dominant centre-right party. Listing his past support for Mitsotakis—appointing him to key posts and backing his leadership bid—he insisted he holds no grudge. “Our differences are political and rooted in values,” he said, accusing Mitsotakis of transforming ND into “a blue-painted version of Simitis-era PASOK,” a reference to the centrist-socialist governments of the 1990s and early 2000s.

He described his own expulsion from the party earlier this year as a hasty, pre-emptive move intended to silence dissent. “I didn’t leave the party—Mitsotakis expelled me,” he said, calling the decision unprecedented for a former prime minister and party president. Claiming the current leadership wants to build a “personal political vehicle,” he added: “I’ve seen no admission of mistakes. Mitsotakis is always right, and the rest of us are always wrong.”

Pressed on the growing speculation that he may lead or support the creation of a new party, Samaras avoided a direct answer but acknowledged a recent open letter by 91 public figures urging him and former prime minister Kostas Karamanlis to form a new political force. He called their intervention “encouraging,” noting that polls already test the scenario even though “the party doesn’t exist,” with some surveys projecting support as high as 16 percent. He said he is weighing his decision “calmly and responsibly,” adding: “When I decide, I will explain it clearly to the Greek people. But don’t expect a yes or no today.”

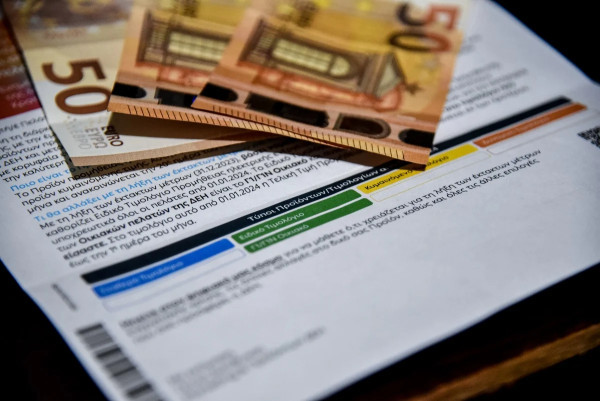

The former prime minister devoted a substantial part of the interview to Greece’s economic pressures, arguing that high energy costs, declining productivity and the persistence of “invisible poverty” are eroding living standards. He accused the government of keeping VAT rates artificially high to project a healthy fiscal surplus and argued that Greece needs a blend of public and EU funding to stimulate growth. Many young Greeks, he said, “cannot realistically start families,” adding that “far more households are on the edge than we admit.”

Samaras also revisited pivotal moments of the past decade, including Greece’s 2010–2015 crisis. He described his clashes with then-chancellor Angela Merkel, claiming she sought to push Greece out of the eurozone “for the sake of an example,” and said he refused. He argued that his own coalition government maintained stability, while the later Syriza-led coalition “created the real damage.” He also referenced personal health issues during those negotiations, saying he worked “around the clock” despite eye surgery, as a rebuttal to past character attacks.

On foreign policy, Samaras condemned what he sees as Athens’s excessive accommodation toward Turkey. He criticised Greece for hesitating to lay an energy cable within its own declared Exclusive Economic Zone while remaining silent on Ankara’s plans with the Turkish-occupied north of Cyprus. He accused European states of hypocrisy for selling weapons to Turkey while championing democracy in Ukraine. He also pointed to recent tensions with Libya, North Macedonia and Egypt, arguing that Greek diplomacy has grown “confused and passive.”

Samaras described today’s New Democracy under Mitsotakis as “an ideological construct that is no longer ND,” claiming the leadership operates like a corporate board and “tolerates no dissent.” He expressed pride in the party’s historical legacy but “deep sadness” for what he views as its current state.

Closing the interview, Samaras warned that Greece faces serious demographic and migration challenges and must adopt long-term strategies rather than rely on “slogans and short-term management.” He insisted that political participation remains essential: “Democracy depends on citizens voting and standing for office. If people withdraw, democracy itself withers.”