Greece is once again turning its attention to persistent tax evasion among freelancers, as new data from the country’s Independent Authority for Public Revenue reveals that nearly half of them continue to declare incomes so low that they fall under imputed taxation rules.

The situation has remained largely unchanged for years, reigniting debate over the need for a policy shift—one that reduces bureaucracy, increases transparency and introduces tax incentives that make honest reporting more attractive than hiding income.

Despite long-standing concerns, the odds of a thorough tax audit in Greece remain relatively low, and the penalties imposed are often insufficient to deter evasion. International experience suggests that blanket audits seldom work; what does make a difference are targeted, data-driven “smart” audits. Greek authorities are now moving in that direction, gradually rolling out automated checks that cross-reference consumption patterns, asset holdings and banking activity. The aim is simple: once freelancers understand that the system can accurately detect gaps between declared and actual income, their behavior tends to shift.

Transparency in day-to-day transactions is becoming a central pillar of this effort. Greece has already expanded the use of card payment terminals, but officials see greater impact in real-time digital links between cash registers and the tax authority, as well as in the broader digitalization of invoicing through the myData platform. As the tax system gains clearer insight into a professional’s turnover and profit margins, opportunities for artificially lowering reported income diminish. Many countries are now moving toward fully electronic invoicing, eliminating paper receipts that can be manipulated or lost, and Greece is edging in the same direction.

Still, no tax system can rely solely on audits and technology. For professionals to report their real earnings, the financial incentive must be there. Greek policymakers are therefore considering lower tax rates on the first tier of profits and more generous deductions for expenses supported by official invoices. The hope is to encourage both freelancers and their clients to favor transparent transactions. At the same time, linking declared income to future benefits—such as pensions, subsidies and access to credit—could help cultivate a more consistent culture of compliance.

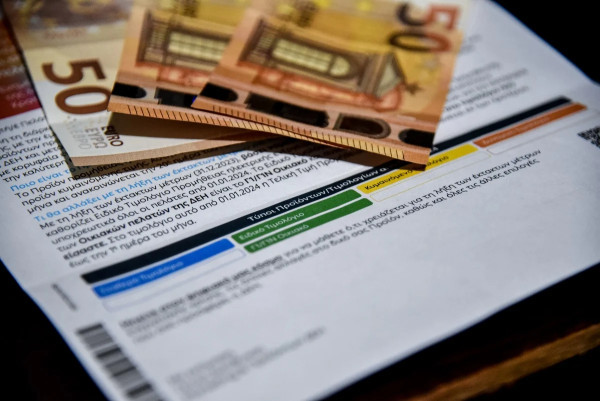

The figures released by the tax authority illustrate the scale of the issue. Nearly 50 percent of freelancers declared an average annual income of just €3,665, or about €305 a month. As a result, more than 387,000 taxpayers were shifted to imputed taxation, which set their income at €13,107 and pushed their average tax bill to €1,815. Even those who avoided imputed taxation declared only €14,552 on average—lower than the reported incomes of salaried workers, farmers and pensioners. Authorities also note a drop in reported business losses, as back-to-back declarations of zero profit are more likely to trigger audits.

Very few taxpayers challenge imputed assessments. Among the nearly 388,000 who were taxed this way, only about 200 formally disputed the tax authority’s estimates—a process that requires full disclosure of assets and living conditions and can prompt auditors to revisit earlier years if inconsistencies arise.

The financial outlook for freelancers remains mixed. In 2026, many will face higher tax burdens as an increase in Greece’s minimum wage automatically raises the minimum imputed income threshold, affecting roughly 400,000 professionals. By contrast, 2027 is expected to bring tax relief for those declaring profits above €10,000, including reduced tax rates and additional incentives for younger workers and families with multiple children.