The so-called “legendary” Goulandris art collection has once again landed at the center of an international legal battle.

On September 23, 2025, U.S. authorities submitted a petition to the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York, seeking judicial assistance in order to obtain evidence from the high-profile art dealer Alexander Apsis.

The request stems from Swiss proceedings before the Court of the Canton of Vaud, where Aspasia Zaimi, heir to Basil and Elise Goulandris, is pursuing legal action against Kyriakos Koutsomallis and the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation.

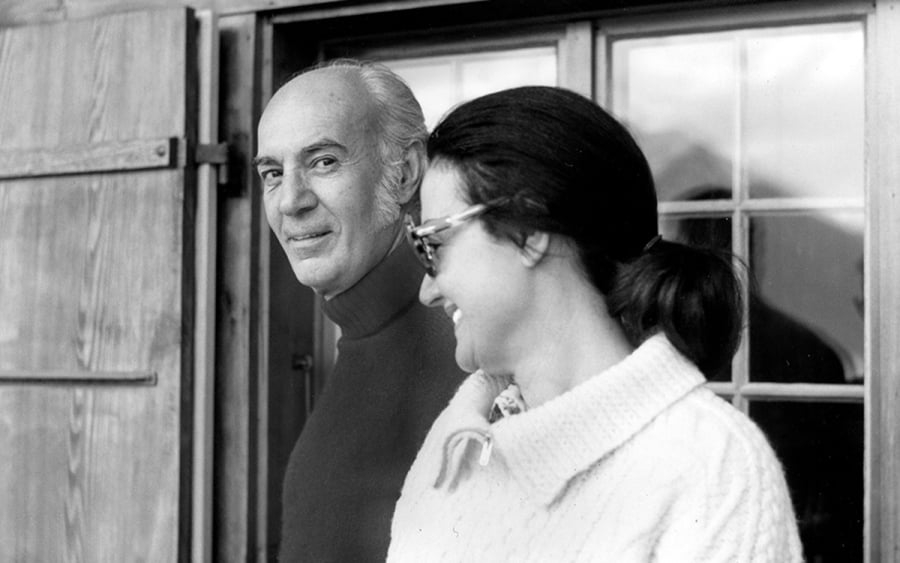

The dispute focuses on the fate of one of the most valuable private collections in the world, with an estimated worth exceeding three billion euros. It includes works by Picasso, Degas, Van Gogh, Monet, Cézanne, and many others. Zaimi argues that these masterpieces, kept at her relatives’ chalet in Gstaad, should have passed into her inheritance following the death of her aunt Elise in 2000.

The history of the collection, however, is complex. According to investigative reporting, 83 works were officially sold in 1985 by Basil Goulandris to Wilton Trading SA, a Panama-based company controlled by his sister Doda Voridis Goulandris, for $31.7 million. Yet testimony from acquaintances of the couple, as well as records of museum loans and private sales, suggest the paintings remained in Basil and Elise’s possession in Switzerland. Zaimi maintains that this proves her uncle never truly parted with the collection.

The controversy deepened in 2016, when the Panama Papers revealed that four shell companies had been established in 2004 by Mossack Fonseca for the purpose of selling works from the Goulandris collection under the umbrella of Wilton Trading. Among the pieces were a Bonnard and two Chagalls. Auction catalogs described them as belonging to a “private European collection,” though the Bonnard, Dans le cabinet de toilette, was tied directly to Basil Goulandris’s name. According to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the companies were short-lived and ultimately owned by his sister Doda.

At the time of those revelations, Kyriakos Koutsomallis, Director General of the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation, insisted that speculation about the collection’s disappearance was unfounded. “The fate of the collection is not unknown, as misleadingly claimed,” he said, “but there is no reason to state where it is located or how many works it includes.”

For Zaimi, the matter remains one of inheritance. She has repeatedly turned to Swiss courts and is now pursuing Koutsomallis and the Foundation directly. What she expects to gain from evidence provided by Alexander Apsis is not entirely clear, yet his presence in the case is telling. A former Sotheby’s specialist, Apsis has operated as an independent dealer since 2001, with a career marked by involvement in multimillion-dollar private transactions.

His name has surfaced in connection with tax probes, transparency concerns in the art market, and controversial provenance chains.

The petition in New York does not determine ownership of the contested artworks. If approved, however, it will authorize subpoenas and the collection of evidence within the United States, which would then be transmitted to the court in Lausanne for use in the ongoing proceedings.