Although Greece does not impose direct state censorship, the report finds that journalists and media outlets often operate under pressure not to challenge the government or expose scandals. Human rights groups and journalists’ associations note that major publishing houses frequently avoid uncomfortable topics, citing fears of job loss, threats to journalists’ safety, and the widespread use of defamation lawsuits as tools of intimidation.

One of the most prominent examples came when Grigoris Dimitriadis, the former chief of staff to the prime minister, sued reporters and media outlets investigating the wiretapping scandal that rocked Greek politics. Although the courts ultimately dismissed the case on public interest grounds, the episode drew attention to the growing use of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, or SLAPPs, which burden journalists with costly legal battles designed to deter investigative reporting.

The State Department also references the European Commission’s 2024 Rule of Law Report, which recorded seven cases of harassment or intimidation of journalists in Greece, down from sixteen the year before. Yet press freedom organizations reject the idea that conditions are improving, describing the Commission’s findings as “overly positive” and inconsistent with the daily reality faced by reporters, activists, and civil society groups. They warn that minimizing the severity of the problem risks encouraging further government encroachment on media independence.

Concerns extend beyond the courtroom. In May, journalist Rena Kouvelioti was attacked by an unknown assailant while covering a story about illegal construction. The attack, condemned by the Athens Daily Newspaper Journalists’ Union, underscored the physical dangers faced by reporters who investigate sensitive local or financial issues.

At the same time, the report points to structural mechanisms of state oversight. Broadcasters are required to register with the National Council for Radio and Television, and online outlets must display official certification on their homepages. While framed as measures to ensure transparency, these requirements are often perceived as tools of supervision that could limit media pluralism.

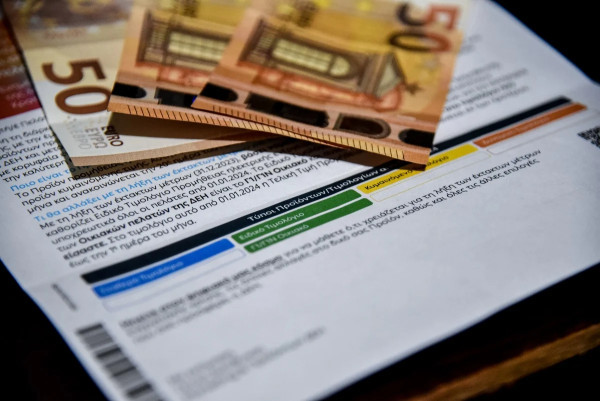

The adoption of the European Media Freedom Act in March was supposed to bolster editorial independence and pluralism across member states. But in Greece, watchdog groups say the legislation has had little practical effect. Most major outlets remain financially dependent on state advertising or closely tied to business and political elites, leaving their editorial independence vulnerable.

Taken together, these pressures—legal, economic, institutional, and physical—paint a troubling picture. While freedom of expression is guaranteed under Greek law, the State Department concludes that systemic weaknesses continue to undermine the independence of the country’s media. Investigative journalism is often obstructed, and self-censorship is widespread, particularly on issues of corruption and abuse of power.