For decades, Greece has lived under the shadow of kakistocracy- government by the least capable and, all too often, the most corrupt. As Giorgos Papanikolaou, Director of Euro2day.gr, observes, this condition was long dismissed as a peculiarly Greek problem, explained away as the legacy of Ottoman rule and the missed Enlightenment, which left the country’s elites socially and intellectually underdeveloped. Even the vocabulary of corruption - bakshish, rousfeti, kotzabasidism - derives from Turkish, as if to remind Greeks that dysfunction was something inherited rather than self-made.

Those who came of age in the late twentieth century, however, began to see the picture differently. Kakistocracy, they realized, is no longer merely «Greek». A generation that once looked westward, hoping Greece might one day resemble more advanced democracies, now looks back with surprise: those very democracies increasingly resemble Greece, entangled in their own versions of institutional decay.

The hope that the financial crisis might force a decisive break with the past has largely evaporated. Education remains a particular weakness. Though tuition is formally free, the system depends heavily on expensive private tutoring, producing exhausted students trained to memorize rather than to think. The building blocks of critical reasoning - analysis, synthesis, and genuine debate - are neglected. Civic education, meant to instill democratic values and responsibilities, is delivered without conviction, more a bureaucratic requirement than the making of citizens.

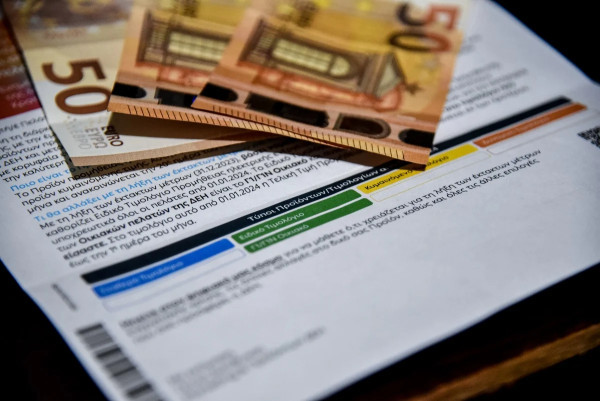

The consequences are visible across society. Trust in institutions is in deep crisis, compounded by economic insecurity. Large parts of the population are left frustrated and angry, recalling the despair of the bankruptcy years. Yet surveys reveal a striking paradox: while Greeks condemn corruption, many are prepared to tolerate it if it delivers competence or personal advantage. A recent QED poll found that voters increasingly prefer a skilled but corrupt politician over an honest yet inept one. As the researchers concluded, «the Greek voter is not immoral - he is selectively tolerant».

The OPEKEPE affair, one of the most notorious recent scandals involving agricultural subsidies and alleged political entanglements, makes the point clear. Four out of five Greeks believe the case undermines the government’s credibility. Yet nearly half admitted they would still support a politician implicated in the affair if he promised hardline measures against migrants and refugees. Cynicism, coupled with selective tolerance, creates a democracy acutely vulnerable to manipulation.

This reflects a deeper structural dynamic. Greece has never cultivated a strong liberal tradition in the European sense. Across the political spectrum, statism has long dominated, feeding party machines that survive on state resources. More recently, the private sector has been enlisted in the same game, trading favors with political power. Meanwhile, the country’s two largest parties together carry more than a billion euros in debt - debt that continues to swell. For many Greeks, this only confirms what they already suspect: that the system is designed not to serve its citizens but to sustain itself.

The outcome is a steady erosion of democratic institutions and a spreading belief that the ends justify the means. As public trust decays, the space opens for «anti-system» politics. History suggests that such disillusionment rarely leads to democratic renewal. More often, it ends in authoritarianism - sometimes cloaked in charisma, sometimes justified as necessity.

For Greece’s political class, this should serve as more than a warning. The question it now faces is not only how to govern. It is how to survive.