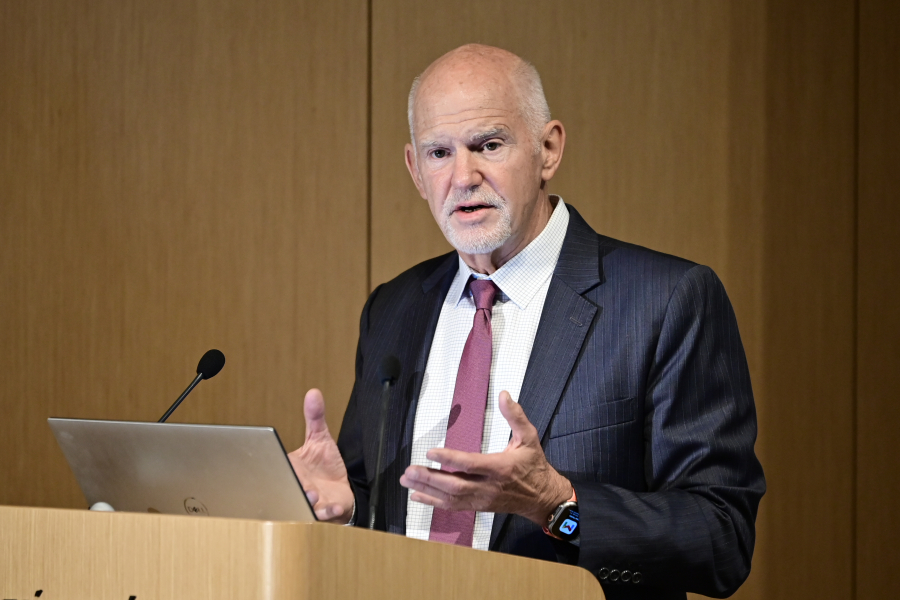

Former Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou has offered a pointed and reflective response to recent remarks by Angela Merkel regarding the eurozone crisis, suggesting that the former German chancellor spoke “three—and a half—truths” about the handling of Greece’s financial collapse. In a public statement titled “The ‘Nothing’ That Was Actually Everything,” Papandreou revisits the early years of the crisis, seeking to reframe its history and underline the lessons Europe still risks forgetting.

Papandreou begins by acknowledging Merkel’s characteristically cautious tone in recounting the events, yet credits her with recognizing certain truths that had been long obscured. The first, he says, is Merkel’s admission that Europe was caught unprepared and failed to understand the true nature of the Greek crisis. According to Papandreou, this was never merely a fiscal meltdown caused by overspending or borrowing. At its core, it was a governance crisis: weak institutions, a lack of transparency—epitomized by manipulated statistics—and a democratic deficit allowed public money to be funneled through clientelist networks instead of being used for sustainable development and social cohesion. He argues that this institutional decay wasn’t unique to the past. Today’s government, led by the conservative New Democracy party, follows similar practices, he says, undermining the country’s credibility and repeating old mistakes by misusing EU recovery funds, agricultural subsidies, and public contracts.

Merkel, he notes, has since acknowledged that she underestimated the severity of the crisis in its early stages. This miscalculation, coupled with the dominant European view that focused solely on budget discipline, sidelined more meaningful structural reforms. The Greek government under Papandreou, he says, tried to push for such reforms—ones aimed at transparency, democratic accountability, and long-term resilience—but instead was treated as a cautionary example. European leaders, particularly in Berlin, approached the Greek case as one requiring punishment, not partnership. Yet, in 2010,

Greece reduced its deficit by five percent—a record among OECD countries. Still, the markets remained wary, which he attributes to the deeper, systemic flaws in the eurozone’s very architecture. Only when the crisis spread to countries like Ireland, Portugal, Cyprus, and even threatened Spain and Italy, did European leaders begin to grasp their collective responsibility. What ultimately reassured the markets was not austerity, but European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s decisive commitment to support member states’ bonds—what Papandreou identifies as Merkel’s second truth.

The second major lesson Papandreou draws is that Greece was unfairly scapegoated, while the roots of the crisis ran deeper and across Europe. At the time, his government sought time and political backing to implement reforms—not more loans. What they needed, he says, was space to correct years of mismanagement and to deliver on a homegrown reform agenda. That plea was not, as Merkel reportedly characterized it, “nothing.” For Greece, for the euro, and for the European project itself, it was everything. Her dismissal of those appeals, in his view, was only “half a truth.”

Merkel has also acknowledged that the decision to involve the International Monetary Fund was hers. At the time, Europe lacked the expertise to deal with a crisis of such systemic depth, and she considered the IMF to be a tough, independent outside actor. This, according to Papandreou, is the third truth. But it also revealed internal doubts within the EU about the credibility of its own institutions. He points out that Merkel and then-Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble favored a debt haircut, but were blocked by European Central Bank head Jean-Claude Trichet and French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

These divisions, he argues, exposed how unprepared Europe was to act cohesively in a moment of existential threat.

Papandreou’s broader warning is that Europe still hasn’t absorbed the most crucial lesson from that period: unity is its greatest strength. When divided, the EU becomes vulnerable—not only to market shocks but also to internal political fragmentation. As Merkel herself conceded, Greece may have been the weakest link, but the entire European system was flawed. The dangers of fragmentation remain, he warns, especially now that the continent faces a new wave of existential threats—from climate change and global pandemics to geopolitical instability and the rise of digital oligarchies.

None of these challenges can be addressed by member states acting alone. Papandreou calls for a bold and coordinated European response, not only in defense and border security but also in education, innovation, sustainability, and democratic renewal. He emphasizes the need to fully mobilize EU financial tools, including eurobonds, to invest in the continent’s shared future. What was once considered radical—like his 2010 call for eurobonds—is now widely accepted as necessary.

In the end, Papandreou insists that Europe’s real power lies not in austerity or punishment, but in solidarity. That, he says, is the ultimate truth still waiting to be fulfilled—a truth born in crisis, and one that could define the future of the European project.